Your independent source for Harvard news since 1898

MONTAGE

Ballet’s Geometry, Torqued

A choreographer’s career taking shape

IN AN overheated basement studio at Barnard College, a dancer twirls with smartphone in hand, eyes fixed on an inches-wide video of the steps she should take. Two others windmill their arms, looking like Olympic swimmers warming up poolside. They’re practicing a piece called “Harmonic,” trying to get the swings’ arc and momentum just right. “It’s really unnatural!” one of them says. Supervising, choreographer Claudia Schreier ’08 instructs, “Don’t let those get too pretty.”

Schreier creates neoclassical and contemporary ballets, and has worked with professionals from companies like the New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, as well as students from top academies like the School of American Ballet and the Ailey School. In this rehearsal, she is setting her dance on members of the Columbia Ballet Collaborative, for the group’s tenth-anniversary performance in April. “To set a dance on” someone basically means to teach them the sequence of steps, but the phrase evokes something deeper: a choreographer’s idea made concrete. Doing this requires that she convey to the dancers not just how the piece should look, but how it should feel.

“Harmonic,” driven by busy, rhythmically complex music by Dutch composer Douwe Eisenga, feels restless, almost anxious. The piece asks the dancers to hold themselves in suspension—Schreier has likened the sensation to the tipping point at the top of a roller-coaster—and also for them to make themselves miss the music’s beat and then rush to catch up. The press of time, of course, is something that ballet dancers—like few artists but many elite athletes—know intimately. Training starts in early childhood; the extent of an individual’s potential is commonly thought to have revealed itself by adolescence; performance peaks not long afterward.

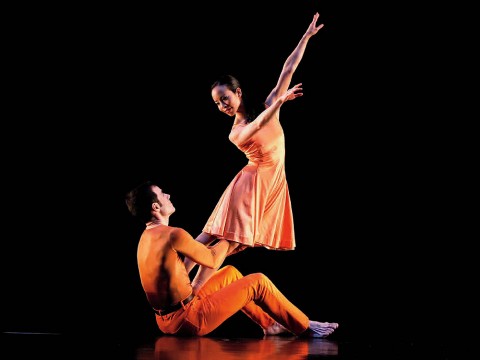

A performance of Harmonic from 2013

Courtesy of Claudia Schreier

Growing up, Schreier studied classical ballet and dreamed of being a dancer, but was frustrated by her physical limitations: “Ballet is built to make you hate yourself. You’re striving for perfection every time, and it’s unattainable.” The trick is to find a sense of freedom in the art, she says, and not fight against its impossible ideals. Then she adds, with a laugh, “It’s the love of my life, so…”

This trajectory seems to have defined her idea of choreography’s essential joy: “You envision how you want to dance, or how you think dance should look, and you’re provided with bodies that can achieve what you can’t.” When Schreier went to college rather than conservatory, she found kindred spirits in the undergraduate ballet company and contemporary dance ensemble: unsure if they wanted to, or could, pursue dance professionally; unsure what they would do instead. “I got to work with these dancers who were—fearless, in a way that I can only truly appreciate now. It’s part of the Harvard mentality,” she continues. “You just go, go, go, go.” Her classmates were energetic and un-jaded, and they trusted her enough to take physical risks and test out her ideas.

Through the Harvard Dance Program, Schreier took classes that exposed her to modern dance technique and training. They stoked her interest in exploring moves outside the ballet lexicon: heaving chests, undulating backs, hips turned in a different way. The challenges of her in-between style became most apparent last spring, she says, when she crisscrossed Manhattan each week to choreograph at the Ailey School and Ballet Academy East. The Ailey students all had ballet training, but gravitated toward modern material, and had to be reminded to hold themselves up and their cores in. On the flip side, with the classically tutored BAE students, “I had to kind of take them on this journey through realizing that I wasn’t trying to undo their ballet training, I was just trying to use it in a different way.”

Solitaire's premiere in 2016, with dancers Unity Phelan, Da'Von Doane, Zachary Catazaro, and Joseph Gordon

Courtesy of Claudia Schreier

Pieces like “Harmonic” torque ballet’s usual geometry. The shapes look familiar, but the way the dancers get into them seems less placed, and more organic. The rhythm is deceptively loose. At the same time, Schreier’s work often seems governed by a sense of cool rationality. At times, the dancers look like marionettes testing the hinges of their bodies, systematically measuring their range of motion. The way she arranges them in space is reminiscent of Muybridge photographs, breaking down a horse’s gallop or a bird taking wing. Because she never danced professionally, Schreier told an interviewer in 2015, she hasn’t felt confident creating partnered dances. But when she was invited by her mentor Damian Woetzel, M.P.A. ’07, to show new work at the Vail International Dance Festival last summer, a duet became the centerpiece. Her piece “Solitaire” begins with three male dancers dexterously spinning a female soloist into various positions, then supporting her in triumphant, acrobatic lifts with her limbs fully extended. Then two of the men exit; in Schreier’s telling, “It goes from very presentational and very regal, and all of a sudden, everything goes awry.” Scored with Alfred Schnittke’s dissonant strings and tinkling music-box piano, the woman gets maneuvered, almost manipulated, into different shapes by her partner. He holds her in what comes to seem like Svengali-like sway; at one point, she’s almost completely hidden from the audience’s view, encased in his arms and torso. The romantic ideal so central to many pas de deux—of femininity made virtuosic, and put on display—takes on a disturbing cast. This is one of Schreier’s most narrative works, and in it, exploration of form gives way, just a little, to feeling.

This summer, Schreier will return to the Vail festival, and present two evening-length performances of her work at New York’s Joyce Theater. Only recently has she gained a stream of commissions sufficient to enable her to leave her day job in arts administration and pursue choreography full-time. (Her work has also been enabled by a program at the New York Choreographic Institute and a fellowship from NYU’s ballet center, both offering financial support and studio space.) Dancers, Schreier jokes, can be fatalistic, and she’s come to accept that her career will be unpredictable. She sees her recent successes less as growing momentum than as a run of good luck: “It makes me appreciate the moment more, because it’s not promised.” A recent knee injury—and her thirtieth birthday—triggered another realization about her craft: “The beauty of it is, it can be forever. Dancing, I would be done by now.” As a choreographer, her career is just beginning.

After the last run-through of that day’s rehearsal, the Columbia dancers wait for Schreier’s notes. She begins by thanking them for their good work; her biggest critique is that everyone is anticipating the music too much, so they’re a little ahead of the count. Instead, she tells them, “Sink into it.”